Previous (Pitch Recognition) – Next (coming soon)

CHAPTER 3: Understanding musical scales and knowing which type of scale you’re in at any given time

This will turn you from an amateur into a pro!

HOW TO PRACTICE THIS CHAPTER: This chapter is a “once in a while” thing, meaning that you don’t need to return to it more than once or twice a month. After all, we’re not trying to turn you into a pianist here but only give you extra background to become a better singer. You just need to broadly understand it. You can then come back to it next week or in a couple of weeks and refresh your memory. Please spend half your time today on the first two chapters (1 and 2) and the rest of your time on reading THIS chapter. Your mission is to LEARN THE MELODY AND FEEL of each chord/scale type that we discuss here.

HOW TO PRACTICE THIS CHAPTER: This chapter is a “once in a while” thing, meaning that you don’t need to return to it more than once or twice a month. After all, we’re not trying to turn you into a pianist here but only give you extra background to become a better singer. You just need to broadly understand it. You can then come back to it next week or in a couple of weeks and refresh your memory. Please spend half your time today on the first two chapters (1 and 2) and the rest of your time on reading THIS chapter. Your mission is to LEARN THE MELODY AND FEEL of each chord/scale type that we discuss here.

BASIC UNDERSTANDING OF MUSICAL SCALES

What is a “scale”?

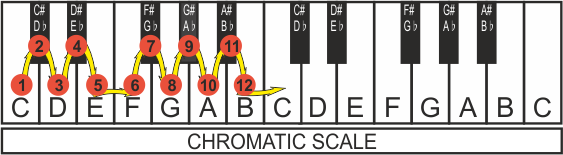

You know that we have 12 tones in Western music, right? If you were to play all 12 tones one after the other, starting from the lowest and ending on the highest – you would play the so-called “chromatic scale”.

Note that in the above example the lady sings “DO-RE-MI…” for each note – this is a note naming system called “solfege”, very popular in Spain and other parts of the world. In the West, it is also very often used to teach children music, though as they get older, they gradually switch to the A-B-C system. In our course we will mostly stick with the more established system where each note is referred to by a letter of the alphabet (A-B-C…etc).

More About Scales

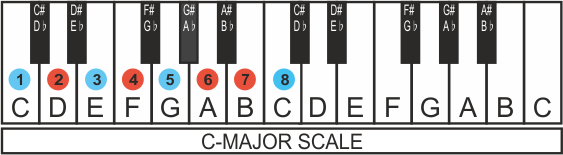

But most scales don’t use all 12 tones. In fact, most only use 7 tones (actually 8 because the 8th tone is the same as the first tone – only an octave higher). Those tones are selected because they “go together” really well. Find out WHY in just a moment. 🙂

The relationships between tones are determined by the distances between each tone, called “intervals”. If you play a chromatic scale, each tone is exactly a SEMITONE (or a “half step”) away from the next.

A semitone is the smallest interval possible in Western music. On a piano keyboard, the distance between a black key and a neighboring white key is always a semitone. In two instances, however, two adjacent white keys (E-F and B-C) are also separated by only a semitone. On a guitar neck, each fret is exactly one semitone away from the next.

Apart from the chromatic, all scales have specific and varied distances between the notes that follow one another and depending on those distances we may call them “major”, “minor”, “diminished” or “augmented” scales. There more scale types and there are also so-called scale “modes”, but we won’t go there just yet.

The scales are named after the first note which starts the scale. For example “C major”. Or “D minor”) Their structure (meaning: sequence of intervals between tones) creates the MOOD or the FEEL of the scale.

Typically, you express the scale of a song by simplifying it and playing only the “most important” tones within it. The conventional way is to use the 1st, 3rd and 5th tone. And this is called a “chord”. That’s why it might sometimes be a little confusing when you see someone play three tones on a piano, but refer to the second tone as the “third” and the third tone as the “fifth”. Now you know why!

What more is there to a chord?

The notes of the standard 1-3-5 chord can be played sequentially (one tone after the other) resulting in what’s called an “arpeggio” (or a “broken chord”) – or all together, resulting in a “triad” (or a three-tone chord).

If you add an extra note to your triad, then depending on the number of that note (counting from the first note which is numbered as 1), you might get a 6th, 7th, 9th, 11th or a 13th chord. For example “C major 7” is the C major chord (C-E-G) with the seventh note attached (B).

You can also have very simple chords with just 2 tones (and it might sometimes be impossible to say if they’re major or minor – or even which chord or key they are in depending on the interval, if they’re played in isolation without the context of the rest of the musical piece), as well as very “dense” chords with multiple notes playing at the same time (which can be pretty tricky to correctly identify as well!).

What is a “Key” in music?

The key of a song is a group of tones – or the scale – upon which the song is based. Typically the first chord in a song will be the song’s “key”. As more chords are played, eventually they always go back to the “key” chord.

What is a “progression” in music?

A progression is a set of chords on which a song is based. In most pop songs only a few chords are used, following the “most pleasing” order. Some progressions are so powerful and appealing that they keep being used and re-used in a lot of popular music.

What is a “round” in music?

When a chord progression ends and returns to the “key” chord – that’s what we call a “round”.

What kinds of chords and scales are there?

As I mentioned above, your chords or scales can be “major”, “minor”, “diminished” or “augmented”, etc. What makes them so is the distance between each note in the scale. Each scale only has 7 notes – but you also always add an 8th note which is the same as the first note, only 1 octave higher).

Most people agree that a major scale sounds “happy”. The distances (intervals) between each tone are: (1) root – (2) whole step – (3) whole step – (4) half step – (5) whole step – (6) whole step – (7) whole step – (8) and a half step leading up to the 8th tone. Click to listen to a major scale

A minor scale sounds “sad” or melancholy – according to most people. The distances between each tone are: (1) root – (2) whole step – (3) half step – (4) whole step – (5) whole step – (6) half step – (7) whole step – (8) and a whole step leading up to the 8th tone. Click to listen to a minor scale

Can you see the differences? The third, sixth and seventh tones are dropped by half a step (relative to the major scale) to give us a minor scale.

Can you HEAR the differences and can you FEEL the mood changes?

And what about diminished and augmented scales? We won’t deal with those yet, but just so you know, the diminished scale drops the third and the fifth tone of a major chord by half a step, while an augmented scale raises the fifth tone by half a step.

These scales are also more on the “sad” or “moody” side and are often used in music to set a more interesting atmosphere.

As you hear the major, minor, augmented and diminished chords – can you make up a melody that would “go nicely” with those tones? (we’ll come back to this in another chapter)

Each scale has its own characteristic sound and melody. Even if you can’t tell (by ear) which KEY the scale is in, you should easily be able to tell whether it’s major or minor. Click to listen an overview of ALL major and minor chords .

With practice you will also be able to identify not just scale variations but also scale “modes” (which we’ll look at a little later in this course).

An important “flavor” can be added to each chord by adding an extra note – or more notes – to it. A very popular “flavored” chord is created by adding a seventh tone (it’s the fourth note in the chord, but it’s the seventh note within the scale) which makes for a very warm and “jazzy-sounding” chord. It’s also used in R&B almost “all” the time.

Here’s a quick overview of “all” 7th chords – but for now you don’t need to worry about any others than just the major and minor ones. But still have a listen: Click to listen .

Why do some tones sound great together while others don’t?

Did you ever hear someone say that “music is very mathematical”? Or even that “music is math applied!” Wanna know why?

Every tone has a frequency. A “frequency” is the number of “oscillations” per second.

Here’s how you can easily understand it: Take a piece of string and swing it in a circle as fast as you can. How many times can you make it go around in the space of one second? Most people can manage to do 5 to 10 rotations with no problem. That is what is called an “oscillation”.

As you’re swinging your string, can you HEAR a “pitch”? A tone of sorts? Whoosh…!

Now, take your guitar and pluck one of the strings. If you could video-record the string while it’s vibrating, then magnify it, and then slow the video right down, you would see that the string is vibrating at a certain speed (number of oscillations per second). You could actually count those oscillations, with a little patience! Obviously a string vibrates much faster than what you could do with that piece of string you were swinging – but it’s the same principle.

So, now we come to the interesting part – for the nerds anyway! 🙂

Each note that any instrument can play, is an “oscillation” – or a “vibration” – in other words it always has “so many” vibrations per second.

For example, the fourth “A” on a keyboard (also called “A4”) vibrates at exactly 440 Hz (“hertz” – so named after the physicist Heinrich Hertz who first proved the existence of “waves” and, among others, measured sound oscillations).

For example, the fourth “A” on a keyboard (also called “A4”) vibrates at exactly 440 Hz (“hertz” – so named after the physicist Heinrich Hertz who first proved the existence of “waves” and, among others, measured sound oscillations).

The next A (“A5” in this case) is exactly one OCTAVE (8 tones) away from A4 and it vibrates at 880 Hz. Exactly twice as fast! It’s like 2 to 1 – a perfect proportion.

The notes between A4 and A5 (and, of course, between all other notes up and down the whole spectrum of notes), are related to each other by similar proportions and so they oscillate at speeds which are mathematically “perfect” in relation to the other tones.

A simplistic way to assign frequencies to all the in-between notes could be like this: you could take the distance between two tones making up an octave and then divide it by 12 and thus arrive at the tuning of each note.

This would work – but wouldn’t sound “perfect.” The mathematical relationships between notes tuned like that wouldn’t be as perfectly (and mathematically) harmonious as we want them to be, so instead we assign frequencies to notes basing on whole-number proportions between each frequency!

You don’t need to know more than this, BUT – if you really want to understand the precise math underlying all this, here’s a quick little video for all you diehards!: Click to listen

So, as you can see, for example a perfect “fifth” relates to the root note with a ratio of 3 to 2 (3:2). which is 660 Hz. A major third relates to the root note like a 5 relates to a 4 (5:4) which is 550 Hz.

Knowing all this, you now understand why some tones sound great together: It’s because their mathematical relationship is “perfect” (meaning: have harmonious mathematical proportions between them)!

Here’s another beautiful example of the relationship between music and mathematics: Click to listen .

What are chord inversions?

When you play a basic chord, for example C major (C-E-G), the first note – also called the “root” note – is the “C”. Next, the second note in the chord is the third note within the scale. Finally, the third note in the chord is the fifth one within the scale.

NOTE: The root note is sometimes called the “tonic” while the third note is called the “dominant”, by the way. And if you ever heard about a “sub-dominant” – it’s the one which is one tone under the dominant, i.e. the 4th one! Enough of that already. 🙂 But now you know! 🙂

So, that’s what a C-major chord looks like. But what if you wanted to play a C-major chord but somehow make it sound “different”?

Inversions to the rescue: you can play each note in a different order! For example G-C-E or E-C-G are still C-major – but different “inversions”. What about C2-E3-G4? That’s a C-major as well!

EXERCISES:

- Please play the C-major triad on your keyboard, first one tone at a time, then all together at once. Now invert the order.

- Using the known intervals that each major scale must have in order to be a “major” scale – can you now play the D major chord?

- Can you play ANY major chord? Remember the “major melody” and listen for it when you play ANY starting tone.

- Can you do the same with minor chords?

- Sing a major triad (the three main notes, first, third and fifth). Remember the FEEL of those notes.

- Now sing a minor triad – and also memorize the distinctly darker and sadder feel.

- Now, take all the exercises above and do them BACKWARDS – from highest to lowest tone. 🙂

Previous (Pitch Recognition) – Next (coming soon)